Currently Reading

Find me elsewhere:

Bookish Q & A

Yes, another one, but I really like this one. Thanks to Tajana (*sighs*), who found this on Tumblr and shared it on her BookLikes blog!

- 1: Currently Reading

- A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel (French Revolution: fictional biography of Robespierre, Danton, and Desmoulins) -- just finished today, in fact.

- Joseph Fouché by Stefan Zweig (French Revolution and Napoleonic Empire: nonfiction biography)

- 2: Describe the last scene you read in as few words as possible. No character names or title.

April 1794: Two of the novel's main characters, plus a number of others, are guillotined. -- History books tell us that the third main character will be guillotined three months later.

- 3: First book that had a major influence on you?

To an equally great extent:

- The various collections of Greek mythology that we owned (they taught me to value courage and intelligence -- my favorite hero was Odysseus; my favorite deity, you've guessed it, Athena -- and they gave me a first inkling of just how far the history of mankind actually goes back);

- The books by German adventure novelist Karl May (they taught me to respect all people equally, regardless of their national and ethnic origin, as well as to value friendship and, again, courage, and they fed into my curiosity about countries and cultures other than my own),

- Astrid Lindgren's Pippi Longstocking books (they taught me that girls can go absolutely everywhere they want to), and

- Otfried Preußler's Die kleine Hexe / The Little Witch (it taught me that in the face of a setback, perseverance and cleverness equally pays off; if you stick to your guns and use your head you will still prevail in the end -- even if you are seemingly outnumbered and outranked).

- 4: Quick, you're in desperate need of a fake name. What character name do you think of first?

Elizabeth Bennet.

- 5: Favorite series and why:

So many! But if I had to name one, at the moment, I guess I'd say Hilary Mantel's Cromwell trilogy. (A trilogy with the third book yet to be published counts as a series, right?)

Mantel is a phantastic writer -- exquisite, seemingly spare, but incredibly "immediate" prose that instantly puts you into her characters' places (and inside their heads) --, her historical research is impeccable, and she has managed that rare feat to make scores of readers (including myself) rethink their assessment of a man who, heretofore, has widely been regarded as one of history's great villains. Oh, and anyway, I'm fascinated with the Tudor Age.

- 6: Public library or personal library?

These days, personal library -- I like to own and be able to keep the books I read. Growing up, however, I had a library card for years and gobbled down everything they had to offer.

These days, personal library -- I like to own and be able to keep the books I read. Growing up, however, I had a library card for years and gobbled down everything they had to offer.

- 7: What is the most important part of a book, in your opinion?

The fact that it was written at all!

- 8: Why are you reading the book you're currently reading?

Both of them, in a general sense, because I'm interested in history and I love France (which makes an interest in the French Revolution sort of a given).

The book by Mantel, in addition, because ever since having read her Cromwell books I've wanted to explore her writing more extensively, so all things considered this was a proximate next choice. Also, it came in handy that it's this month's More Historical Than Fiction group read.

The Fouché biography by Stefan Zweig came highly recommended by a friend, and it makes for a great companion read -- Mantel's book ends with the deaths of Danton and Desmoulins, and this bio not only tells the rest of the story of the French Revolution, it also sheds an interesting sidelight on the man who, inter alia, brought about Robespierre's downfall, and who managed the rare (and rather frightening) feat of keeping his position as one of the surreptitious chief powers "behind the throne" under Napoleon, never mind that the ideological winds were now blowing exactly from the opposite direction.

- 9: If you were to publish a book what (besides your real name) would you use for your author name?

Something entirely fictitious -- if I'd be using a pen name at all, I'd want it to be something that couldn't be traced back to my family, and my own life.

- 10: Do you listen to music when you read? Make a mini playlist for one of your favorite books.

For a rock music playlist, see my recent post, A Playlist for Ian Rankin's Inspector Rebus Series.

For a classical music playlist, I give you

Jane Eyre (Charlotte Brontë):

- Felix Mendelssohn, Symphony No. 3 ("Scottish Symphony")

- Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 6 ("Pastorale")

- Jean Sibelius, Symphony No. 1 and Kullervo

- Johannes Brahms, Violin Concerto (op. 77), Double Concerto for violin, cello, and orchestra (op.102), and Quintet for clarinet, violins, viola and cello (op. 115)

- Robert Schumann, music for Byron's Manfred (op. 115), Violin Concerto (WoO 23), and Piano Concerto (op. 54)

- 11: What book fandom do you affiliate yourself with the most?

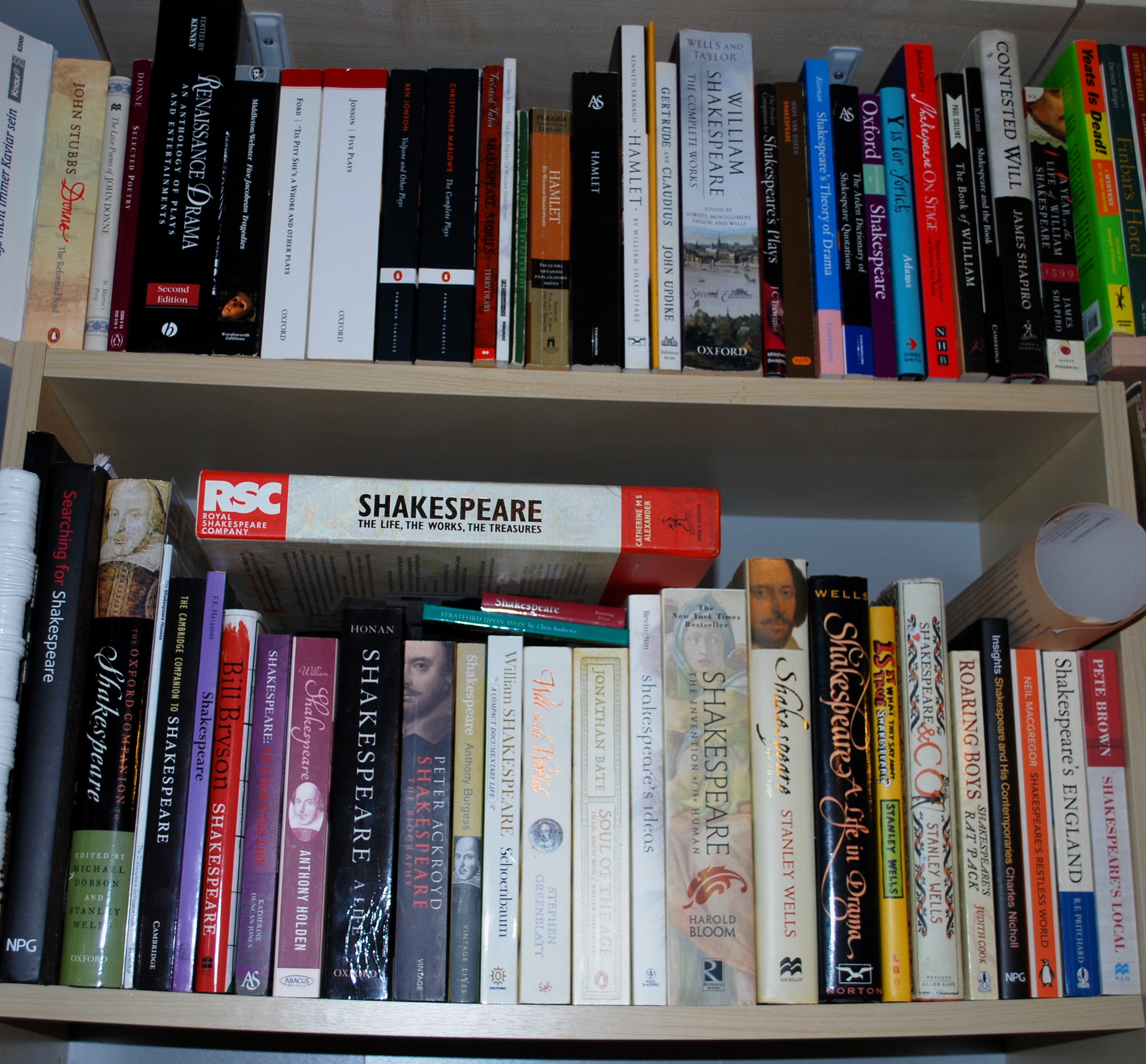

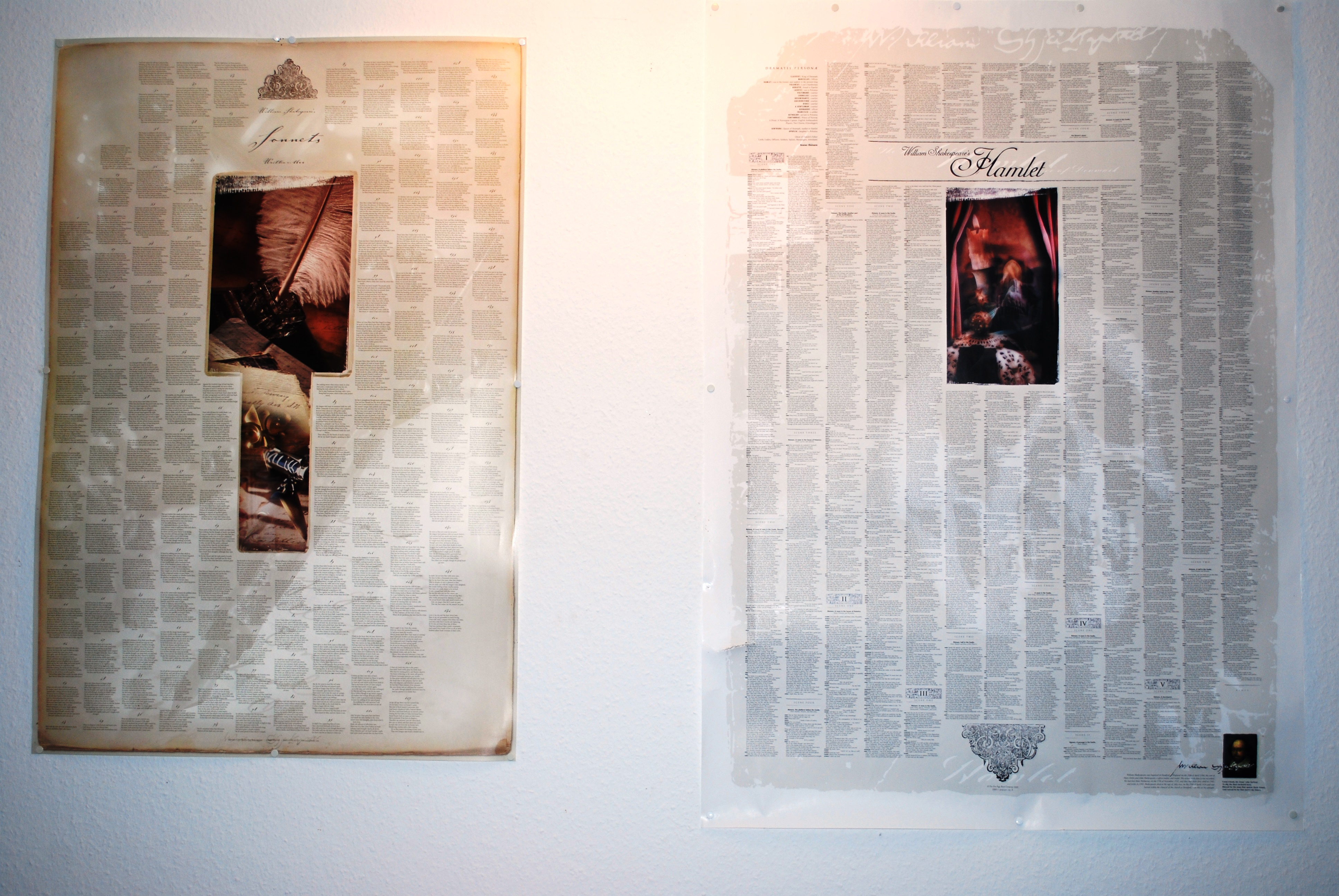

William Shakespeare -- his entire body of work, but in particular Hamlet.

The Prince of Denmark is, without question or competition, the most complex character ever created in literary history, subject to fervent debate practically from the moment he stepped out of Shakespeare's brain onto the Globe Theatre stage and finally onto thousands of other stages all around the world.

The Prince of Denmark is, without question or competition, the most complex character ever created in literary history, subject to fervent debate practically from the moment he stepped out of Shakespeare's brain onto the Globe Theatre stage and finally onto thousands of other stages all around the world.

When precisely the realisation hit home with me what a truly unique character, and what a truly unique piece of writing Hamlet is, I can no longer even tell. All I know is that it was a gradual process: for a long time I was turned off by the Prince's apparent wavering and by the play's sheer length; as well as its gutwrenching atmosphere and – apparent – utter hopelessness, and in no small part also by its uncharitable stance towards its two female characters, Gertrude and Ophelia. Yet, eventually its unique power got through to me and firmly took hold of my brain, unmix'd with baser matter.

I collect Hamlet editions, both in print and on DVD -- and I have, in recent years, created a website dedicated to my own interpretation of the play and, of course, the Prince's character: Project Hamlet. The chances that I'll ever be able to realize my vision of the play in real life are nil for all practical purposes, of course ... but nevertheless one can dream, can't one?

- 12: Tell one book story or memory (what you were wearing when you were reading something, someone saw you cry in public, you threw a book across the room and broke a window, etc.)

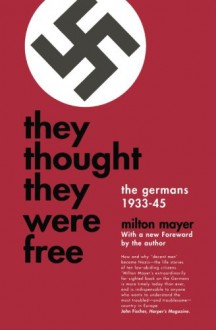

I read Milton Mayer's They Thought They Were Free on the train, on the way to Erfurt (Thuringia / formerly East Germany), approximately in 2010. The book is actually a rather brilliant analysis of the mindset of ordinary Germans in the years from 1933-45, but its cover (literally) raised all sorts of red flags with my fellow travelers, and I got a couple of rather suspicious stares and big, unconcealed frowns. Which reaction however, particularly at a moment when parts of (primarily, though not exclusively) Eastern Germany were, not for the first time since the 1990 German Reunification, going through an uncomfortable spell of neonazis cropping up, I found decidedly encouraging!

I read Milton Mayer's They Thought They Were Free on the train, on the way to Erfurt (Thuringia / formerly East Germany), approximately in 2010. The book is actually a rather brilliant analysis of the mindset of ordinary Germans in the years from 1933-45, but its cover (literally) raised all sorts of red flags with my fellow travelers, and I got a couple of rather suspicious stares and big, unconcealed frowns. Which reaction however, particularly at a moment when parts of (primarily, though not exclusively) Eastern Germany were, not for the first time since the 1990 German Reunification, going through an uncomfortable spell of neonazis cropping up, I found decidedly encouraging!

- 13: What character would be your best friend in real life?

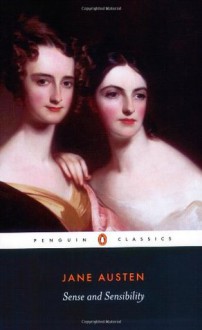

Probably either Elinor Dashwood or Jane Eyre (or both).

I kind of want to say Lizzie Bennet and Portia (from Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice) as well -- you just gotta love women who can stand up for themselves -- but I'm afraid both of these would make me too much aware of my own imperfections, and they probably would be somewhat less forgiving about them than I'd expect the above two to be. As literary heroines, I ever so slightly prefer Lizzie Bennet and Portia to Elinor Dashwood and Jane Eyre, however (with regard to Elizabeth Bennet, see also no. 29, further down).

- 14: Favorite item of book merchandise?

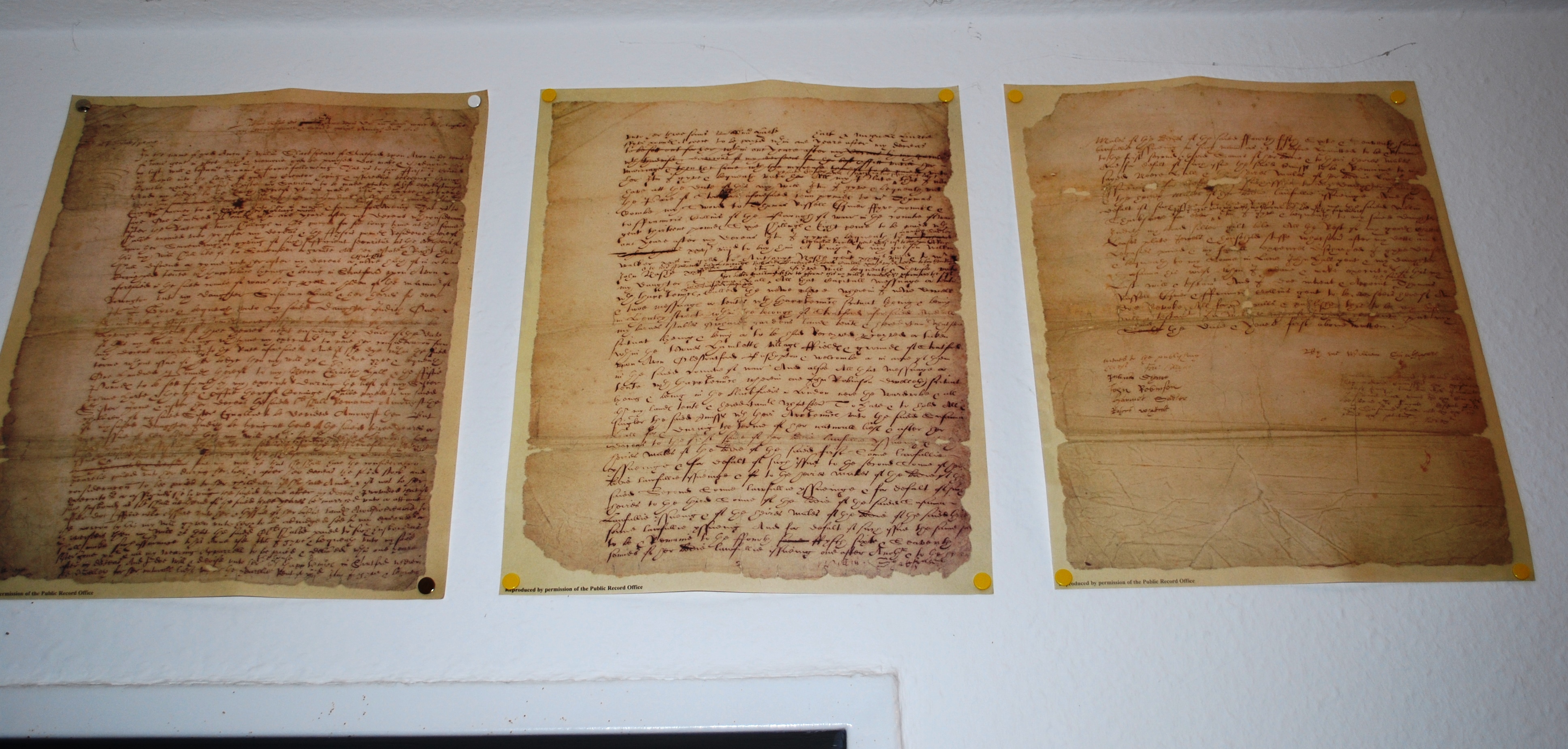

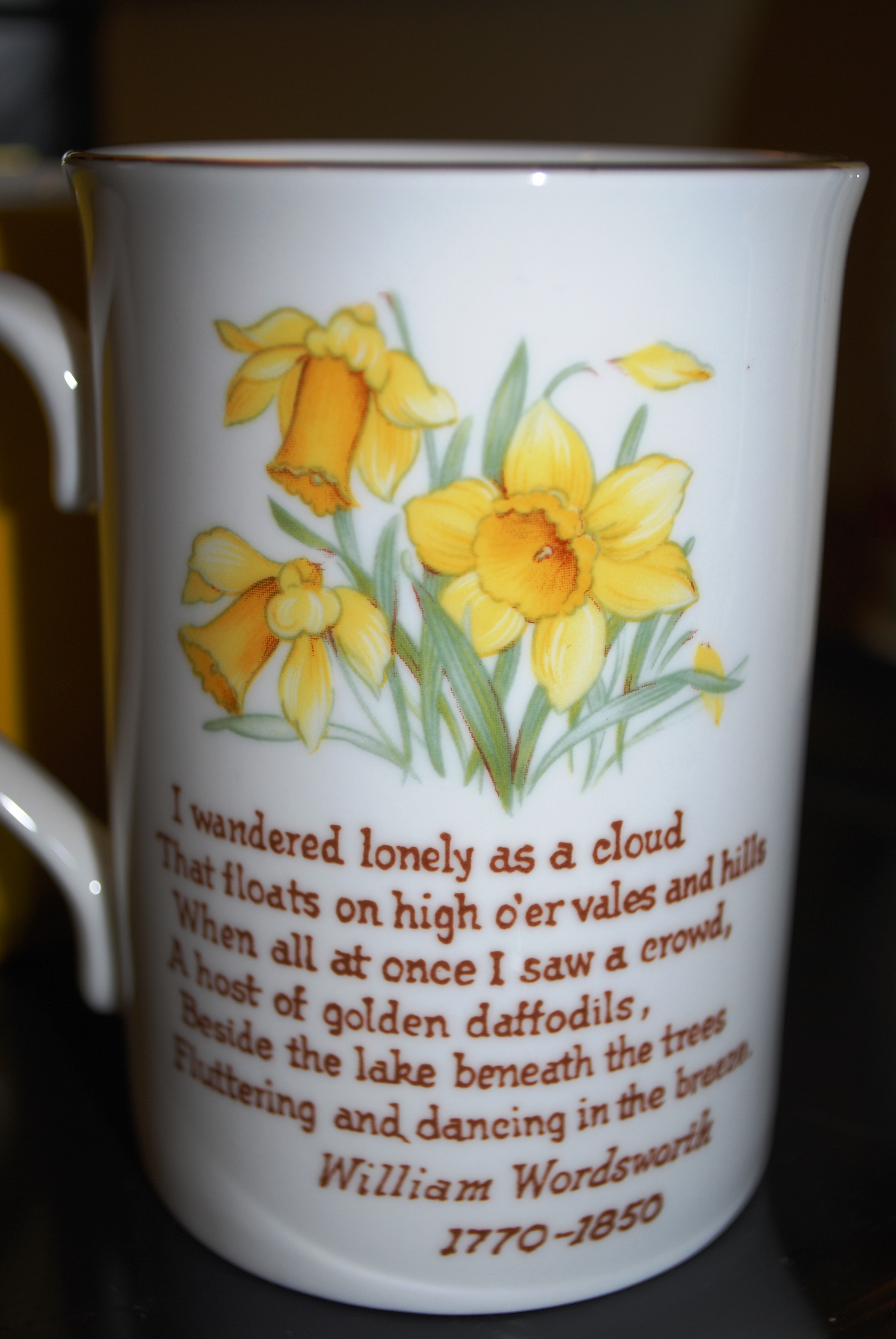

My Shakespeare posters (Hamlet, the sonnets, and his testament), Shakespeare refrigerator magnets and mugs, and mugs relating to other literature classics.

- 15: Post a shelfie.

See above (nos. 3 and 11) and my recent post, Shelfies, Part 2.

- 16: Rant about anything book related.

Major pet peeve: Unrealistic female characters in historical fiction.

Do your research, authors (and I'm looking at you, women authors, in particular)! Your story is just going to lose credibility overall if you ignore the social and cultural realities of the period you're writing about. That doesn't mean that you have to make all of your women shy, demure, obedient little creatures if you're writing about a time, and a society, that didn't exactly endorse gender equality. People are people ('scuse the cliché), and women didn't just wake up to self-assurance and strength of character at some point in the second half of the 20th century. Women's Lib has made it easier for women to match professional achievements and "outward" social standing to their abilities, and it has (at least up to a point) removed the stigma of unacceptable behavior from women asserting themselves. But giving them a freedom and power they wouldn't have had in reality, or reducing them to stereotypes (shrew, manipulative bitch, demure wallflower, obedient housewife, younameit) isn't the answer when writing about a time and place that didn't provide today's opportunities -- it's just lazy writing, period.

- 17: What do you think about movie/tv adaptations?

If they're faithful to the book and pay attention to core production values (social / historical / local authenticity, quality screenwriting, good actors, etc.), they can really add to a story by bringing it to life. In rare circumstances, if everything comes together, they can even shape my mental image of a character to the exclusion of whatever I have imagined him / her to be like before.

Examples:

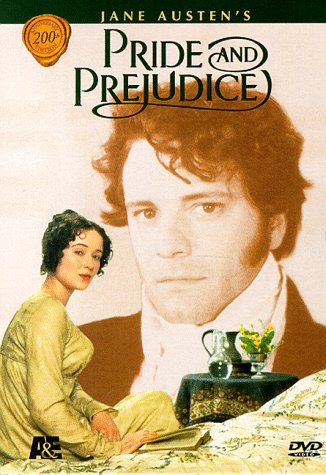

* Mr. Darcy -- Colin Firth in the 1995 BBC adaptation of Pride and Prejudice,

* Colonel Brandon and Edward Ferrars -- Alan Rickman and Hugh Grant in the 1995 movie adaptation of Sense and Sensibility (Brandon / Rickman in particular),

* Mr. Thornton -- Richard Armitage in the 2004 BBC adaptation of North and South,

* Sherlock Holmes -- Jeremy Brett in the 1980s ITV / Granada series,

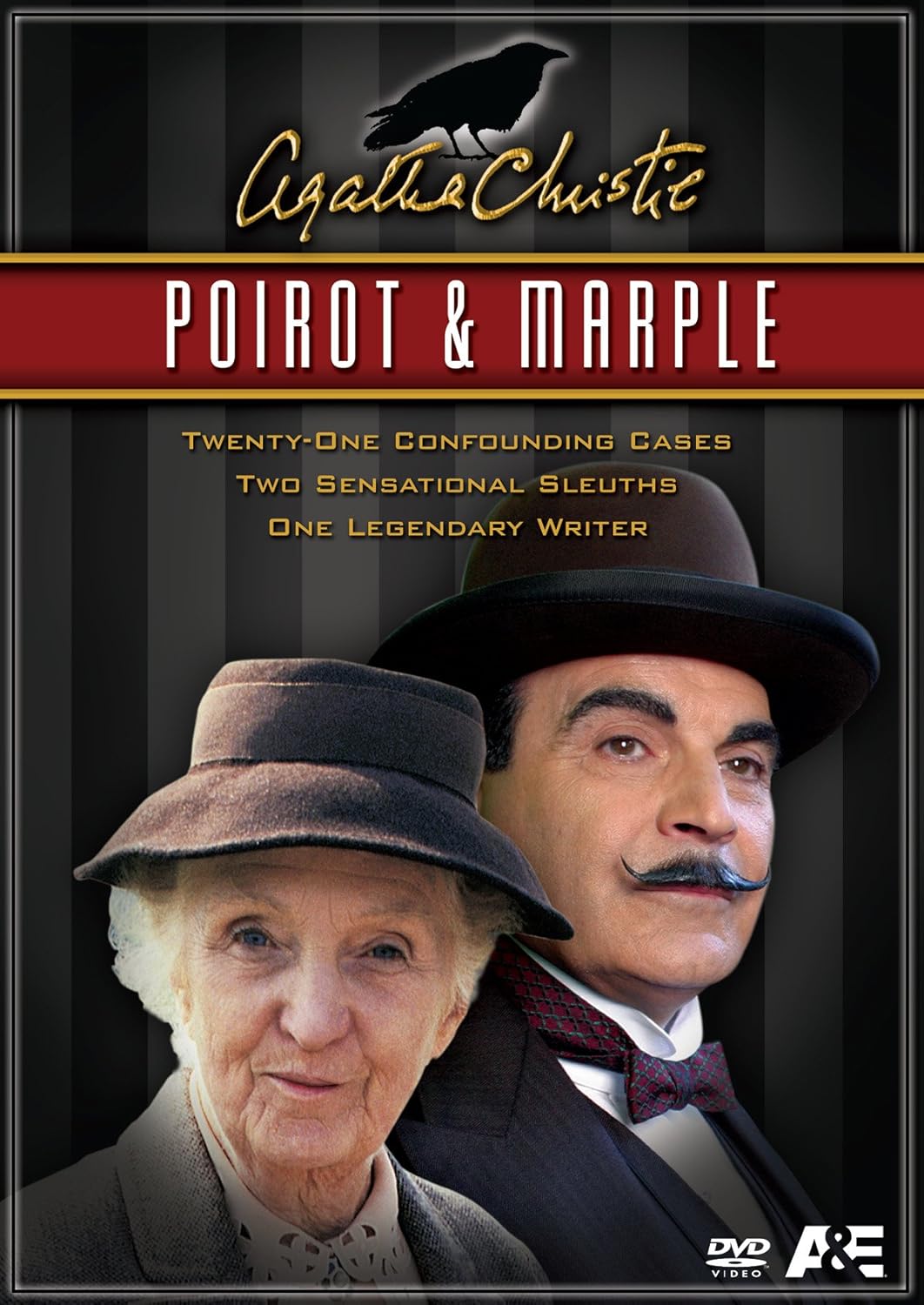

* Hercule Poirot -- David Suchet in the 1990s ITV series,

* Miss Marple -- Joan Hickson in the 1980-90s BBC series,

* Harriet Vane (Lord Peter Wimsey's wife-to-be) -- Harriet Walter in the 1980s adaptations of Strong Poison, Have His Carcase, and Gaudy Night.

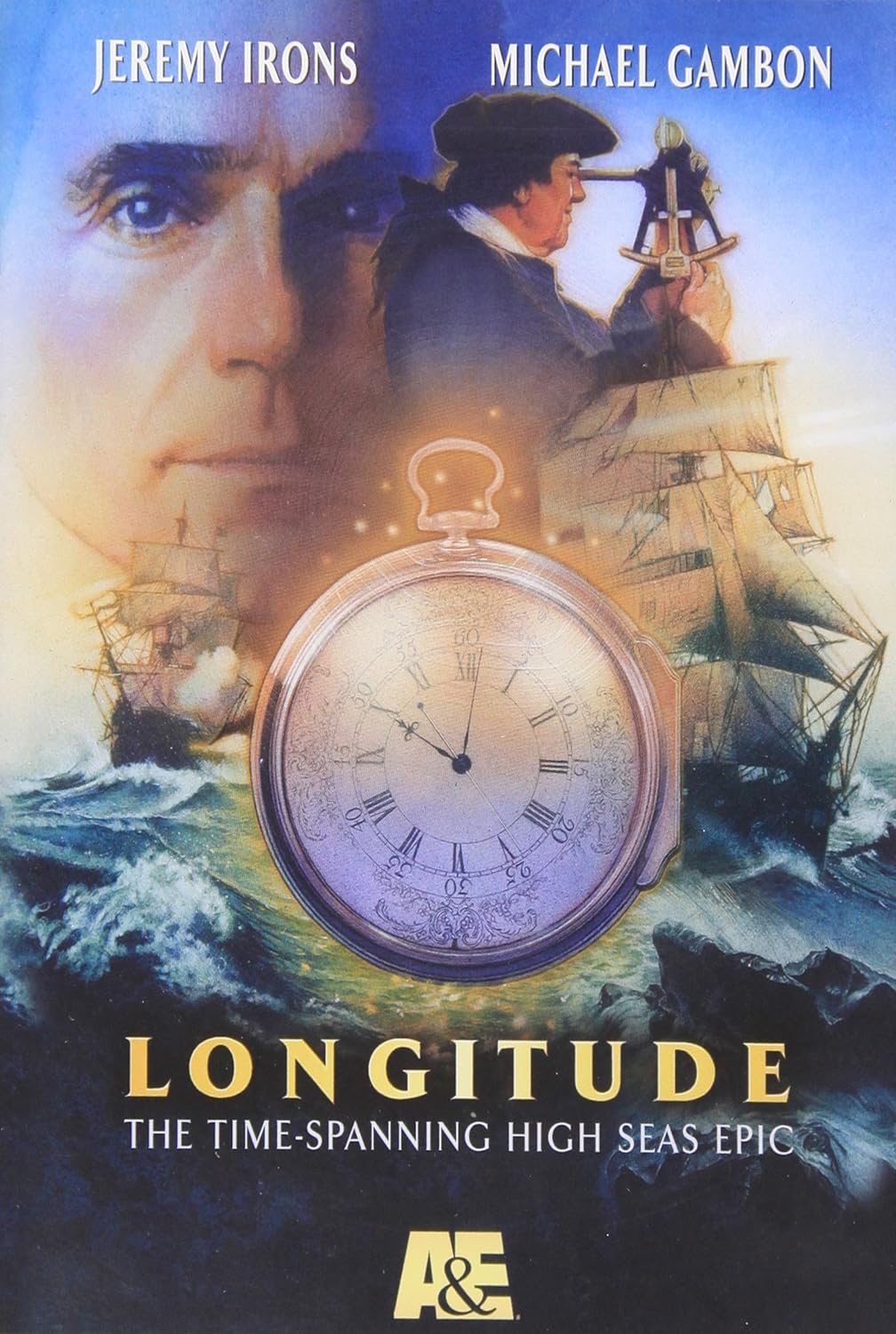

In even rarer circumstances, they may add extra layers of complexity and depth to an already interesting book. Example: the TV adaptation of Dava Sobel's Longitude, which contrasted the 18th century story of John Harrison (Michael Gambon, in the adaptation) with the 20th century story of Rupert Gould (played by Jeremy Irons), who rediscovered and restored Harrison's timekeepers, and whose story was not likewise part of Sobel's book.

In even rarer circumstances, they may add extra layers of complexity and depth to an already interesting book. Example: the TV adaptation of Dava Sobel's Longitude, which contrasted the 18th century story of John Harrison (Michael Gambon, in the adaptation) with the 20th century story of Rupert Gould (played by Jeremy Irons), who rediscovered and restored Harrison's timekeepers, and whose story was not likewise part of Sobel's book.

Sometimes -- more likely, in the context of TV series than in the context of stand-alone movies -- I will forgive a limited degree of unfaithfulness to the literary original(s) if it's a necessary consequence of the transition from page to screen, as long as the core elements of the book(s) are preserved. Examples:

* Most, though not all of Ellis Peters's Cadfael novels that were adapted for the screen,

* The Inspector Alleyn series,

* The Wallander adaptations starring Kenneth Branagh.

On very, very rare occasions, I may even make an exception and forgive fairly blatant unfaithfulness to the books. They've got to give me a really good reason to do that, though. Like, for example, casting Pierre Brice and Lex Barker as Karl May's heroes Winnetou and Old Shatterhand. Yep -- that'll do it, especially when dealing with preteen and teenage me ...

Generally speaking, though ... screw up production values, or materially deviate from the book(s), and I'll move on to something else after having taken one look at the adaptation and decided it's obviously not for me. And unfortunately, that seems to be the case more often than not!

- 18: Favorite booktuber(s)?

Don't have any.

- 19: A book that you call your child?

None.

Companions, best buddies, consolation, inspiration, brothers and sisters in crime, all that -- yes. "Child" is off; that sort of attitude annoys me in authors, too.

- 20: A character you like but you really, really shouldn't?

In Mantel's A Place of Greater Safety, for the longest time, Robespierre. I knew going in that he turned against his former associates and made himself into the chief architect of The Terror of 1793/94 -- but I have to admire Hilary Mantel for her ability to make me, as a reader, get inside his head and agree with him right from the start of her book (which begins with his, as well as Danton's and Desmoulins's childhood), and to also keep my sympathy for him up for the better part of the novel. It was only towards the end of the book, after he began to turn tails on his more moderate confederates, that I was no longer able to follow him -- and my feeling is, that was at least in part because Mantel herself was struggling with his character at that point, too.

Anyway, it interestingly turns out that what she did with Cromwell actually has a precedent in her writing: Cromwell, too, after all had firmly been pigeonholed as one of history's great villains before she came along and turned everybody's opinion around in precisely the same manner in Wolf Hall. And unlike with Robespierre, I have a feeling I'll still like him at the end of book 3, too ...

On another level, though in terms of writerly approach for similar reasons, the protagonist of Ian Rankin's "non-Rebus" thriller Bleeding Hearts. He's a contract killer: the whole book is written from his perspective, and although he's actually telling you how he goes about his latest assignment, you can't help but root for him ... and the reason for this is only partly that his opponents, presumably the good guys, are just SO much sleazier and overall worse than he is. -- Besides, who can resist the notion of a hemophiliac contract killer?!

On another level, though in terms of writerly approach for similar reasons, the protagonist of Ian Rankin's "non-Rebus" thriller Bleeding Hearts. He's a contract killer: the whole book is written from his perspective, and although he's actually telling you how he goes about his latest assignment, you can't help but root for him ... and the reason for this is only partly that his opponents, presumably the good guys, are just SO much sleazier and overall worse than he is. -- Besides, who can resist the notion of a hemophiliac contract killer?!

- 21: Do you loan your books?

Rarely, and only to people of whom I'm sure they (1) will treat them well and (2) will return them to me, even without having to constantly be reminded to do so.

- 22: A movie or TV show you wish would have been a book?

Again, so many! To name just a few (and I know that there are novelizations of some of these, written on the basis of the screenplays -- I wish I were / had been able to read these stories as novels written *before* the screen versions were made, though):

* Casablanca (inspired by a play -- Everybody Comes to Rick's -- but as we've come to know it, written for the screen first)

* Dead Poets Society

* The Crying Game

* Thelma and Louise

* Fresa y Chocolate (Strawberry and Chocolate)

* The Piano

* Farinelli

* When Harry Met Sally

* Before Sunrise

* The Foyle's War series

* Chinatown

* Citizen Kane

* M

* Fargo

* The Usual Suspects

* Memento

* Se7en

* Prime Suspect (the Granada TV series starring Helen Mirren)

* Endeavour (the spinoff of the TV adaptation(s) of Colin Dexter's Inspector Morse novels, set in the 1960s at the very beginning of Morse's career as a policeman)

* Blue Murder (the Manchester-based ITV series starring Caroline Quentin)

- 23: Did your family or friends influence you to read when you were younger?

Stories have been a part of my life as long as I can remember. One of the first things I learned to do was how to operate our record player and play my favorite recordings of fables, fairy tales and other stories. (The photo to the left was taken when I was 2 or 3 years old; my mom's comment in the photo album reads: "First thing upon returning from a walk: a story!") I dearly would have loved to learn to read even before I was ready to go to school: my mom was advised against it; presumably so that my future classmates wouldn't feel at a disadvantage and hate me (this was in the era of universal peace, love, and happiness). But once I'd been taught the first letters of the alphabet, there was no stopping me. I swiftly proceeded to teach myself the rest of the alphabet on my own, and had finished our first grade textbook before my class had officially even gotten to its halfway point. After that, nothing but "real" books would do ... the more, the merrier.

Stories have been a part of my life as long as I can remember. One of the first things I learned to do was how to operate our record player and play my favorite recordings of fables, fairy tales and other stories. (The photo to the left was taken when I was 2 or 3 years old; my mom's comment in the photo album reads: "First thing upon returning from a walk: a story!") I dearly would have loved to learn to read even before I was ready to go to school: my mom was advised against it; presumably so that my future classmates wouldn't feel at a disadvantage and hate me (this was in the era of universal peace, love, and happiness). But once I'd been taught the first letters of the alphabet, there was no stopping me. I swiftly proceeded to teach myself the rest of the alphabet on my own, and had finished our first grade textbook before my class had officially even gotten to its halfway point. After that, nothing but "real" books would do ... the more, the merrier.

I think if I had not taken to reading on my own, my parents would have tried to make me become interested in books. (Whether they would have succeeded in getting me to do something that, for whatever reason, I manifestly did not want to do is a different matter.) As it was, they occasionally steered the direction of my reading -- you don't typically discover ancient Greek mythology at age five or six on your own -- but it was always steering towards, not steering away from: Even if they had believed in censoring their offspring's literary intake (which they didn't), my mom especially knew better than to make things extra attractive to me by declaring them poisoned apples and therefore untouchable per se.

That all said, my senior high school English teacher in particular had a lasting influence on my reading interests as well: I have her to thank for fostering my interest in Shakespeare ('twas Macbeth and the Sonnets in those days), poetry (Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Sonnets From the Portuguese), and Jane Austen -- she was the one who gave me the copy of Mansfield Park from which grew my instant enthusiasm for all of Austen's work.

- 24: First book(s) you remember being obsessed with?

Those listed under no. 3, above, plus:

* Astrid Lindgren's Bullerbyn (Noisy Village) books

* Otfried Preußler's Das kleine Gespenst (The Little Ghost)

* Max Kruse's Urmel books (I also loved the puppet theatre adaptations that were broadcast on German TV when I was little)

* Ellis Kaut's Pumuckl books (again, including their TV adaptations)

* Else Ury's Professors Zwillinge (The Professor's Twins) and Nesthäkchen series

* The Three Investigators series

* Enid Blyton's St. Clare's series

* Walter Farley's Black Stallion books

- 25: A book that you think about and you cringe because of how terrible it was?

Fifty Shades of Grey

(And obviously the quality of the writing is only one of that book's myriad problems.)

- 26: Do you read from recommendations or whatever book catches your eye?

Both, though if it's a book that has just caught my eye (which happens all the time), I check out reviews and recommendations before I make up my mind to actually place it on my TBR.

- 27: How/where do you purchase your books?

Internet, bookstores, bazars, fleamarkets, garage sales, younameit -- though chiefly, in bookstores and over the internet.

Internet, bookstores, bazars, fleamarkets, garage sales, younameit -- though chiefly, in bookstores and over the internet.

I can't walk by a bookstore without peeking in (and typically, re-emerging with a shopping bag full of books). On the other hand, I wouldn't want to miss the convenience of internet purchases, either, especially since only a small part of the books I read are in German, and if there's one thing I'm not exactly nostalgic for it's schlepping home whole suitcases full of books that I can't get here from a trip abroad – as used to be my recourse more often than not in the good old days before the internet. (That is, these days I still tend to do this, but now of course it's a whole different matter ... I mean, what are all those beautiful bookstores in places like London and Paris for if not to be patronized?!) I've cut down on ordering from Amazon, however, as I don't particularly enjoy the notion of feeding a monster (one that also eats its own employees, at that, not to mention its competitors and, more surreptitiously, its customers). While I still may look for books there, and use the Amazon wishlist function, my actual online purchases are frequently from other vendors.

- 28: An ending you wish you could change?

Almost every ending that involves the death of a favorite character. I don't want to lose my loved ones in real life -- so why should I have to put up with losing them in fiction? (And yes, that's also true if it's a historical novel based on real events and I know the character must needs have died.)

Almost every ending that involves the death of a favorite character. I don't want to lose my loved ones in real life -- so why should I have to put up with losing them in fiction? (And yes, that's also true if it's a historical novel based on real events and I know the character must needs have died.)

- 29: Favorite female protagonist?

Lizzie Bennet, as created by Jane Austen and as faithfully incarnated by Jennifer Ehle in the 1995 BBC adaptation of Pride and Prejudice.

- 30: One book everyone should read?

Just one? Hominem unius libri timeo ...

Just one? Hominem unius libri timeo ...

Seriously, I think it's much more important that people read widely and variedly. Tastes will differ, so does personal experience; for that reason alone, I doubt there can possibly ever be "the one" book that is of equal importance to everybody -- and the more limited a person's reading experience, the greater the risk that they will also have only a limited outlook on life. The greater, consequently, the risk associated with shoving one particular book into their hands and telling them, "even if you don't read anything else in your life, read this."

- 31: Do you day dream about your favorite books? If so, share one fantasy you have about them.

See no. 11, above: Being able to realize one day, against all odds, my own vision of William Shakespeare's Hamlet, as detailed on the website dedicated to my interpretation of the play and, of course, the Prince's character: Project Hamlet.

- 32: OTP or NoTP?

OTP: Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy. (As you've probably guessed by now.)

- 33: Cute and fluffy or dramatic and deadly?

I don't do cute and fluffy. Given my fandom of everything Shakespeare, and given that as a general matter I prefer mysteries and crime fiction to all-out romances (and FWIW, Austen's and the mid-19th century women writers' novels are vastly more than that), I suppose I ought to opt for "dramatic and deadly." Don't really do horror, either, though. A nice balance of different aspects is what is most likely going to keep me interested in the long run.

- 34: Scariest book you ever read?

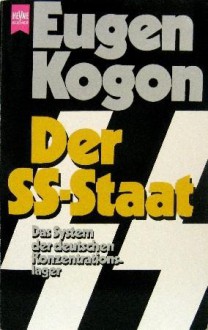

In nonfiction, the books I read about the mid-20th century "labor" / mass extermination camps in which millions of people perished under the Nazis and in Stalinist Russia: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's Gulag Archipelago and Eugen Kogon's Der SS-Staat (The Theory and Practice of Hell). Man is wolf to man, and it's terrifying to behold.

In fiction, it's a tie between several books by Stephen King. Not so much for their splatter factor, though he's certainly come up with plenty of savagery over the years, too; but even if there may be more gruesome horror literature out there (and as I said, I don't read much horror to begin with), what I find absolutely spine-chilling about King's books is that his characters, even the most off-the-wall lunatic, evil, or demoniac, are so completely realistic -- it feels like you could actually run into these people in real life (even if they're not human to begin with). And that's a damned scary notion.

- 35: What do you think of Ebooks?

For the better part of 2 years now, I've appended the parenthetical "Does not and never will own a Kindle" to my (vestige) Goodreads profile / user name, and have been using the image to the left as my avatar ... so there! ;)

I dislike e-readers on a gut level, essentially for the reasons that Ray Bradbury states here (except that you can, of course, put a Kindle in your pocket – but other than that, the touch/feel/smell/experience thing is the same). E.g., I just can't see myself switching on a Kindle for a good night read in bed. Also, I have to stare at a computer screen long enough every day anyway for my job, so when I read for pleasure, I am really looking for a different reading experience; all the more since I've noticed that when I read on a screen, I tend to read faster and skim a lot more, which is not at all the way I want to experience the books I read for leisure. And finally, according to the terms of use you don't actually own the books you "buy" to download them on an e-reader, but they are merely licensed to you, and you can't do anything with them that is not permitted as part of the license. If I buy a book, I want to be sure I own it and can do with it what I please ... ultimately it's as simple as that.

- 36: Unpopular Opinions

... are literature's and every society's bread and butter.

- 37: A book you are scared is not going to be all you hoped it would be?

Pretty much every bestseller that I've ever picked up in the past 2+ decades. I'm extremely wary of hype -- very few books live up to it in my opinion, and the more headlines a book is getting, the longer I will typically wait until I even think about reading it, to see whether it at least seems to be standing the test of time.

- 38: What qualities do you find annoying in a character?

Deceitfulness, stupidity, cruelty, verbosity, vanity, arrogance, self-pity, suggestibility, narrow-mindedness and orthodoxy.

Mainly, though, deceitfulness, stupidity and cruelty. And "annoying" is far too mild an expression for those.

- 39: Favorite villain?

Oh, the epic ones -- Richard III and Mephistopheles (Shakespeare's and Goethe's versions, respectively; for Richard III, also Ian McKellen's movie adaptation). And Hannibal Lecter, as incarnated by Anthony Hopkins.

- 40: Has there ever been a book you wish you could un-read?

No, though there are some books (which -- but for my answer to question no. 25, above -- shall remain unnamed) that really put my forbearance to the test. But even in those cases, I'm ultimately glad I've gone through the experience and formed an opinion of my own. If these books were part of a series, however, I've definitely stopped reading after book one. Even for the sake of literature, there is no earthly reason for prolongued martyrdom.

28

28  20

20