Currently Reading

Find me elsewhere:

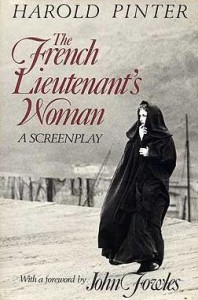

"It is my shame that keeps me alive ... I have a freedom they cannot understand."

"Outside of marriage, your Victorian gentleman could look forward to 2.4 fucks a week," actor Mike coolly calculates after his screen partner (and lover) Anna has read to him the statistics according to which, while London's male population in 1857 was 1 1/4 million, the city's estimated 80,000 prostitutes were receiving a total of 2 million clients per week. And frequently, Anna adds, the women thus forced to earn their living came from respectable positions like that of a governess, simply having fallen into bad luck, e.g. by being discharged after a dispute with their employer and their resulting inability to find another position.

This brief dialogue towards the beginning of this screenplay based on John Fowles's 1969 novel succinctly illustrates both the fate that would most likely have been in store for its title character Sarah, had she left provincial Lyme Regis on Dorset's Channel coast and gone to London, and the Victorian society's moral duplicity: For while no virtues were regarded as highly as honor, chastity and integrity; while no woman intent on keeping her good name could even be seen talking to a man alone (let alone go beyond that); and while marriage – like any contract – was considered sacrosanct, rendering the partner who deigned to breach it an immediate social outcast, all these rules were suspended with regard to prostitutes; women who, for whatever reasons, had sunk so low they were regarded as nonpersons and thus, inherently unable to stain anybody's reputation but their own.

Appearances would have it that Sarah, too, is just such a woman – however, appearances can be deceptive; and herein lies the starting point of the story's social criticism: Realizing that once society has unjustifiedly placed her in that position and that nothing she does will ever wipe away the mark of disgrace she wears as "the scarlet woman of Lyme," Sarah seeks strength in her very role as a pariah; trying to find a liberty not allowed to women of "good" society who are bound by the era's moral prerogatives; and to create a space for herself where she is untouchable because it is too far beyond the accepted social boundaries. In this, she resembles Nathaniel Hawthorne's Hester Prynne (who however, unlike Sarah, actually had committed the adultery she was accused of). But Sarah's attempt to salvage at least a fraction of her sense of self dramatically fails when she is discharged by conservative old Mrs. Poulteney for "exhibiting her shame" by having been seen – against her employer's express prohibition – on an undercliff overlooking the sea across which her supposed suitor, the French lieutenant to whom she owes her less-than-charitable epithet and reputation, disappeared, never to return. Desperate, she literally throws herself at the feet of Charles Smithson, who although recently engaged to a local merchant's daughter has taken more than just a slight interest in her, and who to her has thus become the proverbial white knight in shining armor. Charles in turn, unable to contain his infatuation with Sarah, casts aside the local physician's equally well-meaning and misguided counsel (the doctor considers Sarah's condition a classic case of "obscure melancholia" and would like to see her committed to an asylum) and breaks his engagement, thus incurring social shame himself, to be free for Sarah ... only to find her gone when he returns to take her home.

Faced with the impossibility of creating a screenplay from a novel set in the Victorian Age but told from a 20th century perspective, interspersed with the author's frequent modern-day commentary, in order to maintain that duality, playwright Harold Pinter opted for a "movie within a movie" scenario, allowing modern-day actors Mike and Anna to give the commentary provided by Fowles himself in the book. But more than that, Anna and Mike are also a foil for Sarah and Charles in that they are engaged in an extramarital affair; and while late 20th century morality is obviously different from that of the Victorian Age, they, too, must decide what is to become of their romance. And in both cases, it is Sarah/Anna who ultimately makes the decision: In Fowles's novel, one that invites Charles to respond and whose outcome will lastly depend on his response (the author provides two different conclusions, leaving it up to his readers to determine the one most convincing to them); but in the the two actors's case, Anna presents Mike with a fait accompli, contrasting with the end of Sarah's and Charles's story in the movie.

Sublimely capturing the story's gothic atmosphere with its candlelit rooms, stormy nights and a haunted woman who – particularly when first seen standing at the edge of the Lyme Regis Cobb, oblivious to the winds and raging waves around her – appears more like a ghost than a human being, "The French Lieutenant's Woman" is perfectly cast with Meryl Streep and Jeremy Irons in the dual roles of Sarah/Anna and Charles/Mike: While outwardly quite different (Anna is upbeat but rational, Sarah passionate and vulnerable), both women ultimately find strength within themselves, whereas both men are sensitive and generally quieter, although Charles especially is Sarah's passionate equal once his feelings are stirred. Scored by Carl Davis and also boasting a strong supporting cast, "The French Lieutenant's Woman" won a Golden Globe for Meryl Streep (Best Actress) and several British awards, but none of its five Oscar nominations (Best Actress, Screenplay, Art Direction, Costume Design and Editing – Jeremy Irons unfairly didn't even earn a "Best Actor" nomination). Yet, the movie is a compelling production, bringing to life Fowles's complex characters in a thoroughly convincing, poignant fashion; and Pinter's intelligent, sensitive screenplay undoubtedly had (and still has) an indelible part in its lasting success.

Lyme Regis: The Cobb (June 2009)

13

13