Currently Reading

Find me elsewhere:

For Moonlight Reader: Books With a Difference

Responding to Moonlight Reader's "call for papers (= titles / authors)" -- there are quite a number of excellent lists out there already; anyway, here's my contribution ... or a first draft, at least. Links go to my reviews (or status updates / summary blog posts) to the extent I've written them, otherwise to the relevant BookLikes book page.

Not necessarily in this (or any particular) order:

Dorothy L. Sayers: Are Women Human?

Dorothy L. Sayers: Are Women Human?

Sayers didn't like to be called a feminist, because she was adverse to ideology for ideology's sake, but nobody makes the case for equality and for the notion that a person's qualification for a job depends not (at all) on their sex but solely -- gasp -- on their qualifications and experience more eloquently than she did in these two speeches. (I gave up on the attempt to review this little book when I realized that I was basically fawn-quoting half its contents, but the BL book page lists two very good reviews by others.) Sayers's crime fiction is legendary, of course, but she'd totally be short-changed if she were ever reduced to that ... even to a brilliant book like Gaudy Night (which transforms into fiction much of what she addresses here). This should be taught and listed right alongside Virginia Woolf's Room of One's Own and Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Women.

Moderata Fonte: The Worth of Women

Moderata Fonte: The Worth of Women

If you thought women in the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance didn't know how to speak up for themselves, think again. There's Margery Kempe, Julian of Norwich, Hildegard of Bingen, Christine de Pizan ... and then, there is 16th century Venetian Moderata Fonte. The Worth of Women is, essentially, a witty, pithy conversation among several women preparing one of them (the daughter of another one of their number) for her wedding, and it covers everything from women's daily life and struggle (as such, but in particular vis-à-vis the stupidity and inferiority of the other sex, which without any justification whatsoever has been declared "superior"), their wishes, desires, etc. The young bride, who actually doesn't much feel like marrying to begin with, is consoled over the fact that she really has to (the only alternative being the cloister) by the assurance that every effort has gone into finding her a good husband (i.e., the best specimen from an inherently inferior selection), and receives manifold advice on how to get around him. The whole text reads refreshingly contemporary, very much to the point -- and in part, it is just laugh-out-loud funny. ("Moderata Fonte" was, incidentally, the pen name of a lady actually named Modesta Pozzo, which means ... exactly the same thing: Modest Fountain. [Or Fountain of Modesty.] And yes, I probably should review this book at some point, too -- God knows, I added enough quotes from it on Goodreads back in the day ...)

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Half of a Yellow Sun

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Half of a Yellow Sun

One of my highlights of 2018 and the book that (in large parts) inspired my personal "Around the World in 80 Books" challenge; an insightful, heartbreaking, unflinching, and just all around amazingly written look at the 1960s' Biafra war, post-independence Nigerian society and the human condition as such, by one of today's most brilliant writers, period. Eye-opening in so many ways. (And yes, admittedly this one is on several of those published "must read" lists, too, but in this one instance I don't care. This really is a book that everybody should read.)

Aminatta Forna: The Memory of Love

Aminatta Forna: The Memory of Love

My Half of a Yellow Sun of 2019; the book which alone would have made that "Around the World" challenge a winner even if I'd hate every other book I've so far read for it (which I don't). Trauma, fractured lives and society, love, betrayal, war and peace in post-independence Sierra Leone (1960s-70s and present day). Forna is Adichie's equal in every respect and then some. For a bonus experience, get the audio version narrated by Kobna Holdbrook-Smith: He transforms a book that is extraordinary already in its own right from a deeply atmospheric and emotional experience into visceral goosebumps material.

Xinran: The Good Women of China

Xinran: The Good Women of China

Before she emigrated to the UK, Xinran was a radio presenter in Nanjing: Inspired by the letters she received by women listeners, she started a broadcast series dedicated to their stories, some of which she tells in this book. Her broadcasts gave Chinese women -- firmly under the big collective male thumb for centuries and still considered beings of a lower order today -- a voice that they hadn't had until then; now her books give non-Chinese readers a pespective on an aspect of Chinese society that most definitely doesn't figure in the pretty picture of a modern high-tech society that China would love to present to the world.

Astrid Lindgren: Pippi Longstocking and Lindgren's Wartime Diaries ("A World Gone Mad")

Astrid Lindgren: Pippi Longstocking and Lindgren's Wartime Diaries ("A World Gone Mad")

Pippi Longstocking taught me, when I had barely learned to read, that girls can go anywhere and do anything they set their minds to. -- Lindgren's wartime diaries are tinged with the same sense of humor and profound humanity as her children's books, in addition to containing a spot-on analysis of the political situation in the years between 1939 and 1945 and many insights into her daily life.

Lion Feuchtwanger: Die Jüdin von Toledo (Raquel, the Jewess of Toledo, aka A Spanish Ballad)

Lion Feuchtwanger: Die Jüdin von Toledo (Raquel, the Jewess of Toledo, aka A Spanish Ballad)

A bit hard to come by in translation, but absolutely worthwhile checking out (and an indisputable evergreen classic in the original German): Set during the medieval Spanish Reconquista (the era when Christian princes and armies were wresting the Spanish peninsula back from the Muslims), in Toledo, during a phase when Christians, Jews and Muslims were living together peacefully in Castile; the true-life story of -- married -- (Christian) King Alfonso of Castile and his love for a young woman of Jewish faith. Lots of food for thought on multicultural societies, tolerance, broadmindedness and responsible choices that applies today just as much as it did then. I first read this decades ago and it has stayed with me ever since.

Iain Pears: The Dream of Scipio

Iain Pears: The Dream of Scipio

More on multicultural societies, tolerance, conscience and choices; set in the Avignon area of Provence during three distinct historical periods: the end / breakdown of the Roman empire, the medieval schism of the Catholic church (when the popes were residing in Avignon), and the Nazi occupation of France. All three periods are linked by a mysterious manuscript, and in all three periods the (male) protagonists are guided by a woman who is their superior in wisdom and who becomes their inspiration. Another one of those books that have stayed with me for years and years.

Wallace Stegner: Remembering Laughter

Wallace Stegner: Remembering Laughter

MR mentioned Angle of Repose, and I'd agree that is Stegner's best novel (it's also far and away my favorite book by him); but I do also have a soft spot for his very first novella, written as his (winning) entry in a writing competition, in which all of the hallmarks of his fiction are already present, most importantly the backdrop of his beloved Western Plains and the topic of people's isolation from each other (even when they're ostensibly in company).

Gabriel García Márquez: Crónica de una muerte anunciada (Chronicle of a Death Foretold)

Gabriel García Márquez: Crónica de una muerte anunciada (Chronicle of a Death Foretold)

100 Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera may be the books by García Márquez that the creators of those "must read" lists tell you to read (and I don't exactly disagree), but this brief novella set in a small Columbian seaside town is every bit as worthwhile of notice: A deconstruction, in a mere 100 pages and in reverse chronology, of an honor killing and the society that has allowed it to happen. Completely and utterly spine-chilling.

Actually, any nonfiction by Rushdie (for my money, most of his fiction writing as well, but part of that is on "those lists" anyway, and I know Rushdie's style of fiction writing isn't everybody's cup of tea). I've read some of his essays, but not enough of them yet to make for a full collection, so I'll go with the one nonfiction book of his that I actually have read cover to cover: His memoir of the fatwā years. Unapologetically personal and subjective, even if oddly -- and to me, jarringly -- written in the third instead of the first person; but definitely one of my must-read books of the recent years and one that I have every expectation will stand the test of time.

For completion's sake: His essays are collected in two volumes entitled Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981-1991 and Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992-2002. I'm hoping to complete both of them, too, some day soon.

Graham Greene: Our Man in Havana and John Le Carré: The Tailor of Panama

Graham Greene: Our Man in Havana and John Le Carré: The Tailor of Panama

Two takes on essentially the same topic -- corruption, Western espionage and military shenanigans in Central America --, both redolent with satire and featuring a bumbling spy against his own will as their MC. I'm not a fan of either author's entire body of work, but I find both of their takes on this particular topic equally irresistible ... and unfortunately, they seem to have regained consiiderable topicality in recent years.

Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman: Good Omens

Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman: Good Omens

By which I do not mean the recent TV adaptation but the actual book, as well as (by way of a companion piece) the full cast BBC audio adaptation. Armageddon will never again be as much fun -- but Pratchett and Gaiman wouldn't be Pratchett and Gaiman if there weren't a sharp-edged undercurrent, too: Unlike the TV adaptation with its squeaky-clean looks, the book does not shy away from taking an uncomfortably close look at religion and society. And then, of course, there's Crowley and Aziraphale ...

(Honorary entry from Pratchett's Discworld series: Hogfather. Just because.)

Michael Connelly: Harry Bosch Series

Michael Connelly: Harry Bosch Series

One of the two ongoing crime fiction series that I'm still following religiously and have been, from very early on. Connelly nails L.A., to the point that it becomes a character in its own right in his novels rather than merely a backdrop. Harry Bosch is a Vietnam vet, your quintessential curmudgeonly loner with a big heart, fiercely loyal (motto: "Everybody counts or nobody counts") and hates corruption, grift and nepotism in the LAPD more than anything else. One of my all-time early favorite entries in the series is book no. 6, Angels Flight (which deals with the Rodney King riots and their fallout), but really, Connelly just keeps getting better and better. The TV series starring Titus Welliver as Harry makes for great companion material, but to me the books will always come first. (Even more so now that some of them are actually narrated by Mr. Welliver in the audio versions.)

Ian Rankin: Inspector Rebus Series

Ian Rankin: Inspector Rebus Series

The other long-lasting crime fiction series that I've been following since pretty much forever; for similar reasons as Connelly's Harry Bosh series: Edinburgh is a character of its own rather than mere backdrop; John Rebus (ex-S.A.S.) is Harry Bosch's brother in spirit in virtually every respect -- except that Bosch has a daughter, whereas Rebus has (or had, until recently) his booze -- and like Connelly, Rankin does not shy away from addressing the social and political topics of the day in his novels. For me, Rankin had found his Rebus legs, oddly enough, also in book 6 of the series, Mortal Causes (which deals with the "white supremacy" / neofascist brand of Scottish nationalism), but he, too, just keeps getting better and better.

P.D. James: Inspector Dalgliesh Series

P.D. James: Inspector Dalgliesh Series

From the waning years of the Silver Age of detective fiction (post-WWII through the 1960s) all the way to the New Millennium, James was the reigning queen of British mystery writers, and for a reason. Her friend (and rival for those honors) Ruth Rendell may have been more prolific, but every so often gave in to populism and cliché -- not so James. She was unequaled at setting a scene and creating a suspenseful atmosphere, and in the best tradition of the Golden Age masters, her mysteries always turned on psychology first and foremost. Means and opportunity were important, but it was humans and their relationshp that she was chiefly interested in. I have no doubt that her books will stand the test of time just as well as those of Conan Doyle, Christie, Sayers and their generation of mystery writers.

Joy Ellis: Their Lost Daughters

Joy Ellis: Their Lost Daughters

The second book in Ellis's Jackman and Evans series; an absolute stunner in every single way. Mike Finn and Jennifer('s Books) weren't that enchanted with Ellis's other series (Nikki Galena), and I have only read one other book by her so far (Jackman & Evans no. 1), but be that as it may, this one is completely worth it and then some. Set in the Fen Country, dripping with dark atmosphere, with a likeable and fully rounded pair of detectives as MCs -- and a veritable jaw-dropper of a finale. Oh, and the audio version (of the entire series) is narrated by Richard Armitage.

Peter Grainger: An Accidental Death

Peter Grainger: An Accidental Death

New Norfolk crime fiction series no. 2, and every bit as atmospheric and well-written as Ellis's Their Lost Daughters. This is the first book in the DC Smith series, which centers on a formerly higher-ranking policeman who has chosen to stay on the job as a detective sergeant (rather than go into retirement), so as to be able to actually do hands-on crime solving work instead of being shackled to his desk dealing with police administration. Again, highly recommended, and I am very much looking forward to continue reading the series. -- With this series and those by Ellis, I'm also really, really happy to have found not one but several new series set in a part of Britain that has not yet been written to death.

Donna Andrews: Meg Langslow Series

Donna Andrews: Meg Langslow Series

I am not anywhere near a reader of modern cozies (and though Golden Age mysteries are often lumped into that category, to my mind few of them really belong there) -- I quickly get bored by trademark kinks and similar forms of repetitive humor, and I often find their plotlines, characters and settings unconvincing, shallow and overly sugarcoated. Donna Andrews is the exception to the rule: I probably still wouldn't read too many of her books back to back, but visits to the crazy but comfortable world of her small-town Virginia have become a Christmas reading tradition in the last couple of years that I've really come to look forward to. Favorite entries to date: Duck the Halls, The Nightingale Before Christmas, and Six Geese A'Slayin'.

Jennifer Worth: Call the Midwife

Jennifer Worth: Call the Midwife

Midwifery in London's East End, in the mid-20th century. I'm not even a mother myself, but man, I've never been more grateful for the advances in modern medicine than after reading this book. Well, and other social advances obviously. Gotta love the Sisters, though ...

Jared Diamond: Collapse and The World Until Yesterday

Jared Diamond: Collapse and The World Until Yesterday

Diamond won a Pulitzer for Guns, Germs and Steel, but these two books (particularly: Collapse) are, to my mind, much more relevant to the world in which we're living today; in analyzing both the state of our modern, globalized world (and its chances for a sustainable future) and the lessons to be learned from past societies: those whose choices led them to failure as much as those whose choices led to success and long-term survival. Diamond is anything but a prophet of disaster, but being a scientist, he cannot and of course does not shrink from simple, indisputable facts and realities. At no time have voices like his needed to be listened to and taken seriously as much as today.

Full disclosure: I know Jared Diamond personally; he's a longtime friend of my mother's. That doesn't however impact my belief that his voice, and those of scientists like him, need to be heard now more than ever.

Stanley Wells, James Shapiro, Tarnya Cooper and Marcia Pointon: Searching for Shakespeare

Stanley Wells, James Shapiro, Tarnya Cooper and Marcia Pointon: Searching for Shakespeare

Hard to believe this started life as a National Portrait Gallery exhibition catalogue, but it did: A lavishly, gorgeously illustrated, supersized, book-length (240 p.) showcasing of Shakespeare's life and times; companion to the 2006 exhibition on the NPG's examination of the authenticity of six portraits then believed to be of the Bard (of which only one, the Chandos Portrait, in addition to the famous First Folio cover of Shakespeare's works and the statue in Stratford's Holy Trinity Church survived that scrutiny). More informative in both text and images than many a Shakesperean biography or a book on the history of the 16th / 17th century.

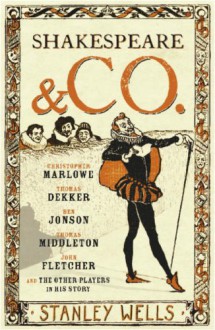

The world of Elizabethan theatre, by the grand master of British Shakespearean scholars and long-time chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Equally engaging, informative and entertaining -- and I'm pretty sure the Bard would have appreciated Wells's not just occasionally pithy turn of phrase.

Antony Sher and Gregory Doran: Woza Shakespeare: Titus Andronicus in South Africa

Antony Sher and Gregory Doran: Woza Shakespeare: Titus Andronicus in South Africa

The future artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company and one of Britain's greatest contemporary Shakespearean actors (himself born in South Africa) -- off stage, a couple -- take the Bard's most controversial and violent play to Sher's home country ... in the middle of Apartheid. Judging by their tour diaries (in essence, this book), it must have been quite a trip.

Final note, for those who are wondering: Golden Age mysteries have been covered by several other list creators here on BL already, so I decided not to replicate that (obviously, otherwise the better part of the entire canons of Arthur Conan Doyle, Dorothy L. Sayers, Agatha Christie and others would have shown up on my list, too). Similarly, while Jane Austen, the Brontes, and several other 19th century writers are unquestionably part of my personal canon, they're also on just about every published "must read" list out there, so there hardly seemed any point in including them here. Ditto Greek mythology. Ditto William Shakespeare (the plays themselves, that is). Ditto Oscar Wilde. Ditto John Steinbeck. Etc. ...

And now that I'm finally about to hit "post", I'm probably going to think of a whole other list of books that I really ought to have included here!

Salman Rushdie: Joseph Anton

Salman Rushdie: Joseph Anton Stanley Wells: Shakespeare and Co.: Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Dekker, Ben Johnson, Thomas Middleton, John Fletcher and the Other Players in His Story

Stanley Wells: Shakespeare and Co.: Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Dekker, Ben Johnson, Thomas Middleton, John Fletcher and the Other Players in His Story 9

9  12

12